My next book will examine the history of reindeer (Rangifer tarandus) translocations across the globe. Reindeer—the semi-domesticated form of caribou—have been central to human life in the Arctic for millennia. They are crucial partners in the fight against Arctic climate change, because their browsing can keep shrubs at bay, thus increasing albedo and cooling local climates. But across the Arctic, reindeer populations are crashing. They have retreated from roughly half their 19th century range, and their populations have dropped by 56% in the past decade. Translocating reindeer herds to viable habitats will be critical as warming reduces the utility of current range. Yet how do we move reindeer—and other threatened species—in a rapidly changing world with complex geopolitical boundaries?

Reindeer translocations have a long and fascinating history. Since the 17th century, reindeer translocations have been core to larger colonial projects of extraction and colonial settlement. Reindeer were translocated to distant islands, first to provide protein for the itinerant whaling labor force, and then to provide a reliable food source for European settlers attempting to negotiate Arctic environments hostile to European livestock such as cattle. Beginning in the late 19th century, North American powers moved reindeer herds—and their Indigenous Sámi herders—across the Atlantic ocean in an effort to settle Indigenous peoples themselves, transforming them from nomadic hunters and gatherers of wild caribou into ranchers of domesticated reindeer. After World War II, Sámi herders themselves took control of certain translocation projects, complicating the nature of wildlife and subsistence economies.

Moving animals about the world has never been just about taking an individual or herd and putting is somewhere else. Rather, it has always involved questions of power, social relations, and visions of a desired future. This project asks: how can we best move reindeer and caribou—and other threatened species—in a rapidly changing world with complex geopolitical boundaries? I argue that close attention to the historic successes and failures of earlier reindeer translocations will improve the chances that climate-change motivated translocations will succeed.

Reindeer translocations have a long and fascinating history. Since the 17th century, reindeer translocations have been core to larger colonial projects of extraction and colonial settlement. Reindeer were translocated to distant islands, first to provide protein for the itinerant whaling labor force, and then to provide a reliable food source for European settlers attempting to negotiate Arctic environments hostile to European livestock such as cattle. Beginning in the late 19th century, North American powers moved reindeer herds—and their Indigenous Sámi herders—across the Atlantic ocean in an effort to settle Indigenous peoples themselves, transforming them from nomadic hunters and gatherers of wild caribou into ranchers of domesticated reindeer. After World War II, Sámi herders themselves took control of certain translocation projects, complicating the nature of wildlife and subsistence economies.

Moving animals about the world has never been just about taking an individual or herd and putting is somewhere else. Rather, it has always involved questions of power, social relations, and visions of a desired future. This project asks: how can we best move reindeer and caribou—and other threatened species—in a rapidly changing world with complex geopolitical boundaries? I argue that close attention to the historic successes and failures of earlier reindeer translocations will improve the chances that climate-change motivated translocations will succeed.

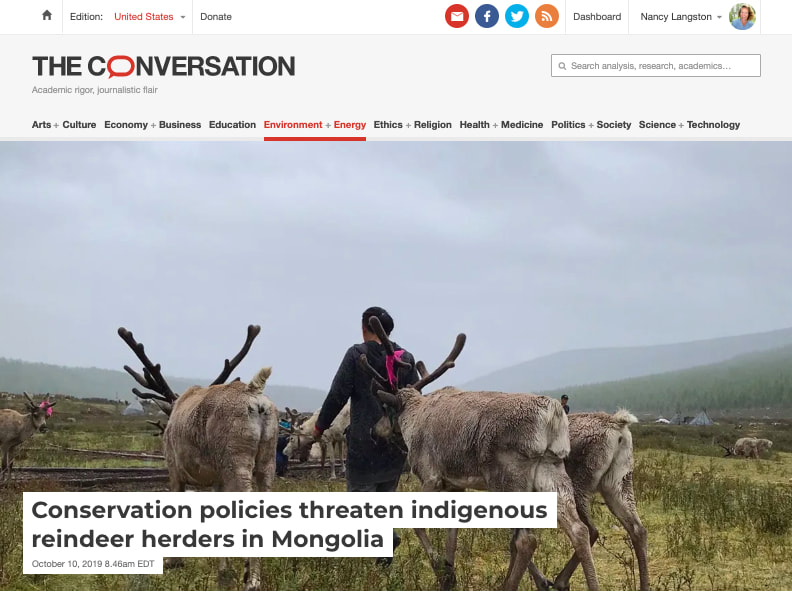

A Voyage to the Reindeer People: Conservation and Climate Change in MongoliaDeep in the sub-Arctic boreal forest of far northern Mongolia lives an indigenous tribe who are among the world’s smallest ethnic minorities and last reindeer herding nomads. The Tsaatan, as they’re known, have been buffeted over the last century by political and economic shocks, growing resource and environmental pressures, and significant impacts of climate change. But today they’re also facing another danger which they feel may be just as big a threat as any of these to their survival: the conservation policies of the Mongolian government.

Read more in The Conversation |

Mining the Boreal North: Reindeer, the Sami, and Colonial PowersResource extraction decisions are not simply about wilderness preservation or development. Colonial histories continue to shape decisions about who has access to the land.

Read more in American Scientist |

Woodland caribou, climate change, and extractive industriesIn May 2018, woodland caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou) were declared functionally extinct in the United States. The last remnant population in the Selkirks Mountains of Idaho dwindled to three lone females. In the Lake Superior basin, a genetically distinct population of woodland caribou nearly met the same fate in February 2018. Populations in Quebec, Newfoundland, and Alberta are dwindling as well. Across the Canadian north, woodland caribou have disappeared from roughly half their 19th century range. Is climate change dooming woodland caribou? Or are managers using climate change as an excuse to avoid making difficult policy decisions that could save the caribou but antagonize industry and environmental groups?

Read more in Historical Climatology |

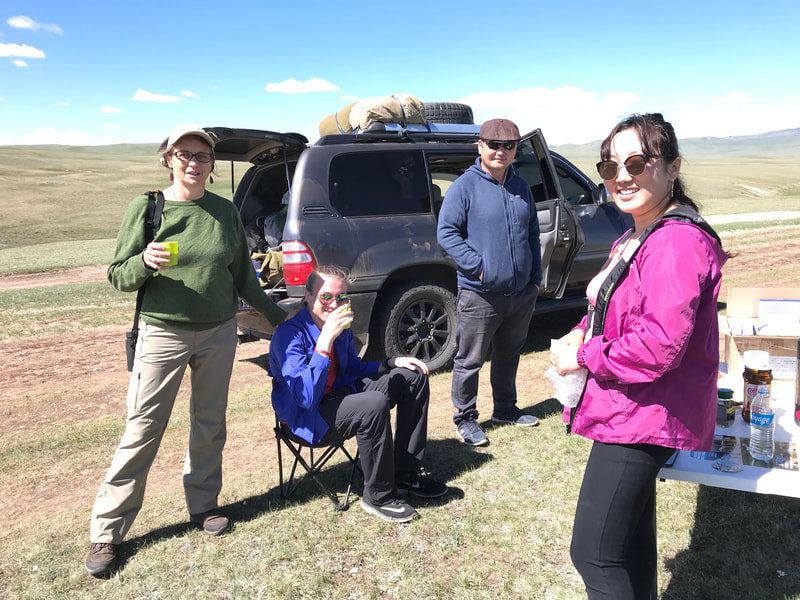

Photo Christian Schroeder

|

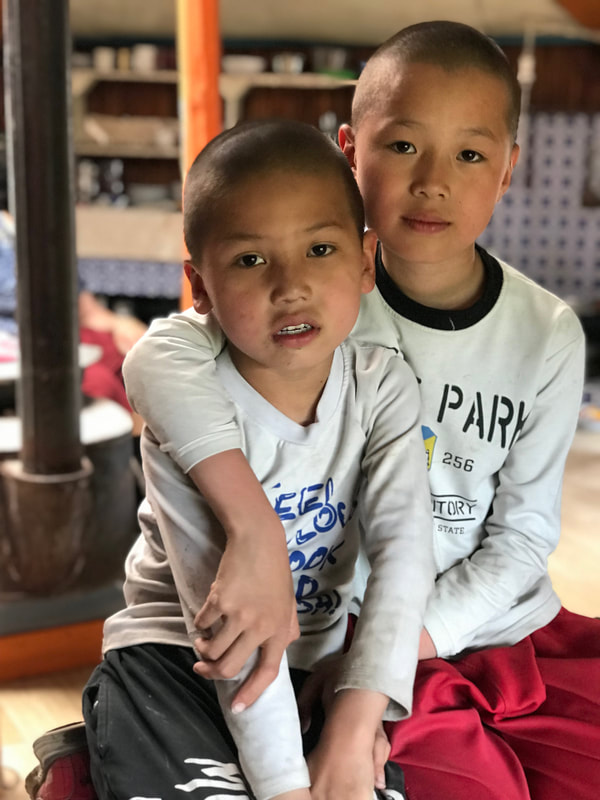

Some of the images we took of the families on the taiga are in the youtube slideshow and the gallery below. Click on the gallery images to enlarge them.